Gaikai, as its own website mentions, is streaming, cloud-based gaming technology which allows gamers to play, preview, and demo PC and console video games for free. Now, what is Gaikai exactly? We talk to CEO and co-founder of Gaikai, David Perry. He discusses Gaikai, which according to him finally makes computing (and gaming) ubiquitous. He discusses what it does, what it changes and the many more possibilities it will have in the future.

What does Gaikai mean? “One of the original founders came up with this name. It’s a Japanese word for the vast, open ocean. Think of it as a word meaning a large open space to be discovered, and that’s what we kind of believe that this is all about. We’re kind of saying to people, “Join us in this voyage to try to explore this space.” The concept is that [on] anything with a screen, you can experience a 6,000 dollar computer [that’s situated] somewhere else. So you don’t need to buy this ridiculously powerful machine, but you have all the power of it in your hands.”

YOU buy this 6,000 dollar machine? “Yeah. We buy the machine, we’ll part with that money, but wherever you are, on a little notebook, you’re able to have so much more computing power. That concept of experiencing one device through another is kind of the whole idea.”

How come no one else has ever thought of that? It sounds … logical. “Yeah. It is logical. And it has been thought of. If you go to an airport, they’re sitting typing on terminals when they’re checking your ticket and it’s a very simple terminal with very basic capabilities. But, it’s connected to a supercomputer somewhere else that’s running the entire technical system for British Airways or who-ever. And that’s basically the same concept. It’s just never been done in 3D, with Call of Duty and everything else. The ones at the airport can’t play Call of Duty on everyone’s computer, it just can’t do it. There was no company I could go to, there was no infrastructure I could rent, hire or buy or anything that could just take care of this problem. It all had to be created from scratch: the management software, the server designs, the relationships with the data centers, everything had to be done from scratch.”

So, you’re the first ones who are creating a service like this. Which obviously means that there will be quite a lot of problems at first. What are the problems that you are anticipating? “The biggest problem I think is a business model. Trying to come up with the right business model that works well for this is hard because it’s so new. I have one competitor, so there’s two companies doing this; there’s OnLive and there’s Gaikai. OnLive charges a subscription to use their service and I was just reading the terms of service today, and their terms of service clearly state: if you stop paying you lose everything. You will walk away from everything, all the games you bought, everything is gone. And that’s never been done before. And that’s the problem, trying to come up with a business model.

“They’ve come up with one but I just can’t understand the logic. Imagine you paid a subscription to load iTunes, so you have to pay fifteen dollars every month just to load it. You can listen to previews, but you can not play any music, you have to buy all the music. And if you ever stop the subscription, all the music you’ve bought gets deleted. That’s the model they’ve decided to come up with. And I don’t know how they’re going to try and explain it to people in a way that makes that feel good.

“The second point is, if you read their terms of service, ‘we don’t guarantee you an internet connection, because the internet is unpredictable’, blah blah blah. So that basically means you’re not going to have access to your music whenever you wanted. So you don’t own the stuff you buy and they can’t guarantee that you’ll be able to hear it when you want to; that’s what they’re offering. And that’s really the difference with Gaikai, there’s two ways to go.

“At every point there’s this way and [the other] way, and everytime they went this way, we went [the other] way. It’s very interesting to see how two companies that are doing something similar could do them so differently, and that’s what our whole mantra is. So first of all, our services are completely free. The users don’t pay anything. If you want to try the newest games from whatever publisher, you can try them on our servers and pay nothing. There’s no subscription, no registration and no download or install. I don’t want your personal information, I don’t want to hassle you about anything, just play it. If you like it, buy it, if you don’t like it, we’re done.

“What I’m really replacing is the banner advert that would have been on the page. My competitor is Google, that’s the company I’m going after. When people pay for those banner ads, those are really expensive if you look at how the math works out. And if I can take a piece of that money that is getting wasted on banner ads, when I can turn a visitor into a player it’s much more valuable. So that means I don’t need to inconvenience the player at all for the cost of play, and that is more compatible with people today. People love free.” * Perry shows a video demo of Gaikai as he used it in his own home through a server in Los Angeles. He smoothly switches between games. He goes from World of Warcraft to Spore, no installs, no updates, no hassle, just instant play.*

“So this is not running on this computer, this is running on a different computer. But I’m able to decide; is this the kind of game I’d like to play? So if you think about it, you’d probably try more stuff. This WoW is 15 GB to download because it also has two expansions installed with it. So if you wanted to sit down and get them you would be busy all afternoon with downloading, installing and the patches and everything. But with [Gaikai] you just click it and you’re able to take a look.

“We’ve also worked with Adobe for the last year to get Flash to support this. We’re using the fastest hard drives money can buy, so you get a better performance than a typical desktop would get. You’re gonna find it hard to buy a computer as fast as the ones we have, because it’s the latest in video cards, the latest Intel processors; it’s absolutely top of the line as far as computing goes. Which means that to most people on a computer that’s maybe one or two years old, it will be a premium experience. That’s the idea.“

How far along are you with finalizing the Gaikai platform? “It fully works now. So it’s not like this is still years away or something, I can already do it. You see it in the video; that was me playing it at home.”

So there is already a lot of support from publishers for Gaikai? “Yeah, we’re going to start announcing some of the partnerships. There’s one rule in this business, which is the Achilles heel of this whole thing: this only works for good games. My helping you play a game that is not good is not going to help the publisher at all. It only helps good games, and that’s important. And it’s important for us, because we want to get known that every time we offer you something you know it’s probably good. So we’re not going to be operating a thousand games. The idea is to keep the number of games low, but very good. That’s what will make the publishers want to pay us. We have to be paid, just to be clear, but we get paid by the publisher so that means we won’t have to trouble the consumer at all.”

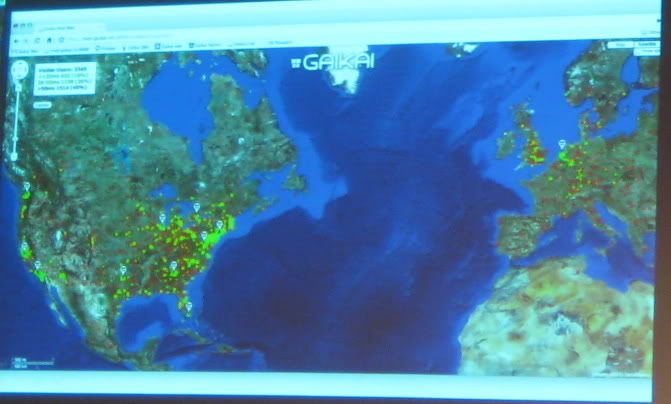

So on what scale will you be launching? How many servers are you planning to have? How many do you have? “The way it works is: the closeness to the server is actually critical, it’s a key thing. So my target is to have 300 data centers in the world. It will take 50 or so just to cover the US. Right now, today, we have 11 data centers live and we add new ones constantly. Amsterdam just came online in the last few days, Paris is next and then London. So we just keep adding data centers. Denver is coming online soon and so is Minneapolis. We just keep going one after the other.

“We have a map of the US. The white dots are the data centers, and every time we add one on it starts lighting up green dots around the area. It has weird and strange patterns because of the way the Internet is wired. So it’s not like you think; you can’t just make a big perfect circle or something. It makes a strange pattern and you can start to see where servers are needed. So we’re launching this month with around 30 million minutes of server time. And that’s what we sell publishers; minutes. By Christmas I will be selling 300 million minutes a month of demo time across the US, and then I will try to replicate that in Europe and that would give me a total of 600 million minutes a month. And that’s plenty of inventory. That’s a lot of demo time.”

Besides streaming games, what future applications do you have in mind for this? “There’s lots of doors that it opens. It affects game development in every possible way. The fact that I’m sending video to this computer here means this user is having that experience. But that video can also be sent to the game designer as well as the users. So the game designer is actually able to watch thousands of beta testers and monitor what’s going on. For example, all these beta testers are playing, but they keep getting stuck somewhere. He can see this and watch whatever the problem is, then he can actually fix that piece of code and reflash the network so the users don’t even need to know. They don’t have to download anything, they don’t have to patch anything. Next time they play, the game designer will be able to actually see whether it has fixed the problem or not. So the idea of real-time tuning is very valuable.

“Another one is real-time crash analysis. If you crash a game, currently they get reports back saying ‘well I was jumping up and down and it crashed’, right? Which is no help at all. So is there a way to improve that using this technology? The answer is yes. So if you crash the game we know on our server that you crashed it, so we can take the last thirty seconds of video and automatically forward it to the developer. You don’t even have to type in reports anymore.

“Then there’s other things too, like cybercafés. I went to a cybercafé and they have 250 gaming boxes and they have to replace them every 18 months because people are paying to use them and therefore they have to be really good. If they want to update a game, like when a World of Warcraft patch comes out, they have to log into each one remotely and patch it. That’s 250 times that you have to log in and patch things, and that’s crazy. If they would use technology like this, they could just buy machines that are simple, that just play Flash or whatever, and then they patch it once on their main server and all the boxes in the room are updated. It could change that whole space completely.

“It is the same for computer software. A demonstration I do is Photoshop loading really really fast, which means now I have Photoshop everywhere I go. They’re 600 dollars a pop, so I don’t want to have a licence key for my office, my home ánd my laptop. I want to be able to just pay them the time I use but have it everywhere I go. And all the files are safe in the cloud. So if I go to England or something I’ve got everything in the cloud ready to go. So that idea of software being ubiquitous, I can then pick up my iPad and continue my Photoshop where I left off. That is kind of neat. The idea that the game goes with you wherever you go, is something that is absolutely do-able today. This is not like something in the future, we can do that right now.”

The whole concept of ubiquitous computing has been something that we’ve all wanted since the dawn of the internet. “I know, and now you can actually do it. Another thing you can do is the sharing of games. My vision that I’m really pushing on the publishers is that I want you to be the first one to discover a new game. You’re the first one in the new Diablo game, for example. First one of all of your friends. I want you to be able to tweet: ‘oh my god, I’m in Diablo 3′, then hit enter, and it sends a link, and if your friends click that link, they are teleported to you inside that game.

“So imagine you’re playing some MMO and you’re running around and you tweet out from within the application ‘hey join me’. Your friends, just like in Star Trek, can beam in around you, and none of them have to register or download or install. None of them know what publisher makes this game, they don’t need to know. They just arrive and they’re now in the world and you’re all playing together. That idea of sharing with no friction is completely possible with this technology.”

There are probably a lot of ideas going around in your head. For example, combining this technology with social networks. “I have a demonstration I’m going to show at E3 of playing MMO’s inside Facebook, without leaving Facebook. So it loads faster than Farmville, because Farmville has to load a flash file. Ours is just connecting you to a video stream out there. It means that I can put Call of Duty or Madden or whatever you want to play in Facebook.”

I immediately have these horrible flashbacks to the CoD:MW2 multiplayer system, IWNet, which has really horrible and problematic connection issues. How stable are the Gaikai Servers? “Well that’s a really good question, a very important question actually. It’s a big concept difference between what we’re doing and OnLive. OnLive is offering service, so ‘come pay us a subscription and play’, which means you really need the answer to that question. It’d better be good or you’ll get really mad, right.

“This is what we do using your website as an example. You have a website where gamers go to. I have publishers that would like access to your gamers. Imagine you’re writing an article about a new downloadable game and you can put one line of Gaikai code on your website, which is one line and no change to the website whatsoever. Every minute that anyone plays that game online on your site we will pay you. And we don’t just pay you a little bit, you get exactly what we get; a 50/50 split.

“Another thing is that the players play the game on your website so the time spent on your website goes up. And the thing that’s important is that the gamer has no expectations of this, so if they’re in Alaska or Egypt or somewhere where we don’t have servers, they just use your site like they’ve always used it. And it’s not like your site says ‘Click here to play this game’. What happens is, they’re reading your article and while they’re reading the article I go have a look and see if there’s a Gaikai server near this person, and if there is the button appears. So the button only appears for the people who are close to one of our servers.

“So because of that we took away the whole problem of ‘is it going to be foggy or not?’, because we pre-test the quality before they get the button; we know they’re close and we know their connection’s good. Every time the button appears we look at where they’re coming from and we can see that we need to have some servers in Alaska or in Egypt.”

How did you start with this idea? “Well, this is what I learned from [working at] Acclaim. The last game I launced at Acclaim was 3.5 GB to download. That really, really, really is a problem. At 3.5 GB, what actually happens is you spend money trying to get them to click, and we would force them to register too, so you would have to register and we’d lose a lot of people there. Then you have to download, and no one can download 3.5 GB like that. Which basically means that they’re all going to do something else. So what you’re relying on is for them to come back to you and then continue where they left off, which actually a shocking amount of people don’t do. They never come back. So they’ve gone through the pain of downloading the file, they’ve got it on their hard drive and they never ever click on it.

“The point is even when you think you’ve succeeded you can still lose. I can’t tell you what is going to happen, I honestly can’t tell you, but I believe very strongly in what we are doing. I think it makes sense. The only problem with the publishers is that they are on two levels. First the publishers that still have the good [development] teams available. We want them to think about ways to modify their games to keep them as frictionless as possible. Then there are publishers who don’t have the original teams anymore, so that as soon as the game is done the team disappears. It means we have to deal with any issues with the games ourselves, and that’s hard work. We had to set up a system to fix other people’s bugs. You have to go into the code, and that’s extra work. Most people don’t even know what we’re doing. A lot of people think we’re just making another version of OnLive or something like that.”

You started in Amsterdam, why there? “My two co-founders are from there. They met each other in Amsterdam and they got this whole thing running and then they got me in. They had a whole different vision. Their vision was to let you play arcade games online so that you wouldn’t have to find an arcade machine. That was what they were trying to achieve. They were working on this very core technology to see how you could do that, and it was very cool. Then they called me and said, would you like to see this running? I had just given a speech about the subject and so I didn’t believe them, and they’re like: “No, no, we saw the speech, and we’ve been working on this actually.”

“They had just gotten WoW running so they sent me a link and that’s what got me involved. From there we evolved the business model, got the funding we have, and 21 staff working on it. So it’s a proper company. At this point it’s just a case of executing and getting all the servers up. The servers are hand-built, all of them.”

This sounds like a really great idea, not only do you get access to top games but you can experience them as they are intended on a top machine!? I’ll be looking out for this as soon as it gets near Scotland!

Oh, and good interveiw by the way! : )