- Format: PSN

- Unleashed: Out Now

- Publisher: Sony Computer Entertainment

- Developer: PlayStation C.A.M.P, Acquire, SCE Japan Studio

- Players: 1

A deserted, nameless street waits, heedless of the ceaseless rain pouring in sheets atop it. Echoing pianos backed by strings and the occasional overtones of a French circus penetrate the night, and two children stumble into view, mute and running from an unknown threat. The stage is undeniably set for a moody art piece to begin, yet something is wrong: have we seen this one before?

Rain is a paradox; it’s the utterly commonplace masquerading as the boldly unconventional. It begins with an intriguing enough premise: a boy awakens to find a girl running from a mysterious beast and, in an effort to help her, follows them into a strange mirror of his own city. However, this parallel world has forsaken the sun and sky for an endless and probably symbolic reign of rain. These aren’t inherently bad concepts, but when introduced with scant smatterings of pseudo-meaningful text and watercolor paintings it can’t help but feel forced. It’s as if Rain’s creators saw just enough like-minded games to trace a copy, but not enough to really understand the meaning and techniques behind such thoughtful masterpieces.

The narrative continues its attempts to tell more with less using short sentences of text projected across the environment throughout your journey; this admittedly looks cool, but serves as another example of a borrowed concept with lacklustre effect. The result is telling less with less, as a lack of real symbolic or atmospheric depth leaves just a few hundred words to create a story simple enough to fit in a children’s picture book, though lacking the witty rhymes or valuable advice concerning the alphabet.

The plot never leaves the young boy’s desperate efforts to save the girl and escape the monster. In fact, it barely does much of anything until the last hour where it gets potentially interesting before cleanly wrapping up with a predictable and unsatisfying conclusion. Though we can’t claim to fully grasp the story’s underlying themes, our working hypothesis is that it’s all a metaphor for death; or possibly just bad dreams, but our money’s on the former.

What’s truly unfortunate is that the narrative is a welcome distraction from the wasteland of monotony that is actually playing the game. Inspirations from 2001′s Ico seem evident, with the emphasis on cooperative traversal in a barren world. This means little more than tapping a button to hop, crawl, and push your way through the city, but it’s not a terribly frustrating way to progress and see the sights. Rain is lacking Ico’s awe-inspiring works of architectural majesty and unparalleled sense of isolation; instead, it traps you in a maze of grey streets with almost no artistic integrity to back the dated muddiness up. It certainly had the potential for some memorable visual effects, since Rain’s premise centres on, well… rain. Everyone’s an invisible shadow of their true selves in this world, except when the downpour plays against them, revealing shapes. However, instead of cleverly using the rain to create splashed and spotty silhouettes, models are simply rendered as translucent “ghosts”, which hardly makes for an evocative effect.

This is admittedly a small complaint, but it’s made bigger by how large a role this transformation from visible to invisible plays in Rain. The mysteriously morose city is infested with deadly monsters and, as a defenceless child, it’s in your best interest to stay out of their way. Avoid the rain and you’re safe, so long as they haven’t already spotted you; this makes the meat of Rain’s play, if it can be called such, as you dart from overhang to overhang while occasionally waiting for a given monster to turn its back. A slim assortment of mechanics are thrown atop this as the game progresses, but they rarely take more than a second or three to grasp, and are certainly never used in even moderately intelligent ways. Simply splash your way forward and, if things happen to go ill, jump back a few seconds and try again. It’s bafflingly dull in practice, and had us sighing in relief that the game only lasted a few deadening hours.

The creation of a minimalistic art piece, more metaphor than matter, is an undertaking that should mean more than simply justifying a tight budget. Rather than promote lazy design and lifted ideas, it should do just the opposite. It should mean that every element of a game, be it a single mechanic or line of text, is a precious commodity that can’t afford to be misspent. Rain seems to think the fact that it’s trying to be art means it can ignore all this, and deliver nothing more than a melancholy introspection for its own sake. The result is a sad distortion of a laudable genre, best left as a poignant warning to those who follow.

]]>

- Format: PC (version reviewed), XBLA, Windows Phone

- Unleashed: Out Now

- Publisher: Microsoft Studios

- Developer: 17-BIT

- Players: 1-4

- Site: http://skullsoftheshogun.com/

General Akamoto is furious; he’s arrived at the afterlife’s shores following a long life of blood and glory only to find his just reward locked behind an endless line of downtrodden warriors, each waiting their own turn for the promised paradise. Having no stomach for patience, he breaks every rule the underworld’s got in it and gathers an army to challenge this Shogun of the Dead, ready to cleave a reckless path through whatever might dare stand before him. Skulls of the Shogun’s simple tale is an apt allegory for the game’s own goals, as it strives to challenge a stagnant genre with a stubborn refusal to simply play by its rules.

Though a rebel in many respects, Skulls of the Shogun makes no bones about its roots in Advance Wars, a defining pillar of turn-based strategy as we know it. Buildings will be captured, resources gathered, and units deployed as armies are pitted against each other in a politely consecutive manner. Where it veers from tradition is in its efforts to break through rigidity and complexity in service of a more free-spirited pace. Movement is no long restrained to a grid, dozens of units are reduced to just seven, and resources are kept so scarce as to make any lasting stalemate an impossibility. A battle should rarely take even half an hour, and anyone intimidated by the genre should find the reliance on a simple trinity of infantry, cavalry and archers a welcome introduction. It’s a solid few rules to manage, and smashing down your enemies only to eat up their skulls, gaining both experience and health for your own troops, has a certain sadistic satisfaction to it.

Unlike katana, however, this loose simplicity is a double-edged sword. The game is rife with imprecision and a feeling of nonchalant hand-waving when it comes to the movement and range of units, with no effective way to estimate who can get where, or who can hit what. This is one of the key fundamentals of any turn-based strategy game, so being reduced to guessing half the time quickly lends itself to an air of ambivalence that encourages sloppy play. This would be easier to ignore if the game had more complexities to compensate, but the dearth of units and mechanics just makes movement and placement all the more noticeable.

We have another bone to pick with this same lack of depth; the best course of action is often easy to spot for anyone familiar to the concepts, making the process of overcoming the AI more an exercise in waiting than strategy. Just make enough archers and the AI’s simple-minded aggressiveness will soon fall victim to a volley of arrows. This makes the brief single-player campaign even briefer, which we managed to complete in under five hours. The Bone-A-Fide release for Steam also adds both a new unit and an extra episode to the campaign that lasts up to an hour or two, which is admittedly considerable, but that says something about the original campaign’s length. A simple yet effectively-implemented array of multiplayer options helps to pick up the AI’s slack and add some much-needed longevity, but it’s still victim to the game’s structural foibles.

Though some games with similarly unfulfilling mechanics can rest on an engaging world and presence, Skulls of the Shogun doesn’t have this luxury. You need look no further than the title to know its theme: a sardonic re-imagining of Japanese warfare starring skeletons. But while this vision is unmistakable, with an Eastern-imbued soundtrack and ample supply of cherry blossoms to boot, it comes off as uninspired and overplayed. The music and writing share an off-putting awkwardness, despite their efforts at endearing eccentricity, and the art feels too familiar to be striking.

Skulls of the Shogun succeeds at its goal of being a thinking man’s Castle Crashers, but in doing so it makes you question the merits of that goal to begin with. It’s quick and fun to learn, but it won’t be long before you’re wanting more and finding less.

]]>

Rumblings began as Giant Bomb’s Patrick Kleppek reported that sources indicated to him that Microsoft would reversing be the Xbox One’s DRM policies that had so crippled them from a public relations standpoint at 2013′s E3. A crashed website and stampede of tweets later, Patrick’s prescient reporting was confirmed by Microsoft releasing a statement of their own.

Though you can read the article for details, in short it’s looking like the 24-hour online check-in will be removed entirely, along with any restrictions on used games and region locking. It’s worth noting that an internet connection is required to initially set up your console, so Microsoft certainly hasn’t been able to address every issue with a single press release. Nevertheless, moving a behemoth like Microsoft to take such a massive change so quickly is anything but easy; but whether it was Sony’s aggressive policies and attacks, the hurricane of consumer outcry, or most likely a combination of these factors and more, it happened. That’s huge, and yet another testament to how crazy just about everything is right now.

]]>

Those looking for something new– or, well, old– to play this Summer can check out Good Old Game’s new 2013 #NoDRM Summer Sale. Serving as the Sony to Steam’s Microsoft, GOG looks to be capitalizing on its more open ownership policy by putting about 85% of their library on sale.

New sales will roll around each day until July 5th, with today’s being their Dungeons and Dragon’s pack 80% off and their Alan Wake bundle 90% off. In addition, the first Torchlight is entirely free for the next 48 hours, which is a lovely catch for anyone who wants some DRM-free Diablo. (Nope, not using the hashtag twice. Nice try, though.)

It will be interesting to see how their strategy of deep and broad cuts can compete with Steam’s own inevitable Summer sale, and how the recent fervour surrounding the philosophy and concept of game ownership will play into the digital realm.

]]>The plot opens with an ancient-sounding fellow beginning an exposition-heavy intro that looks to be as long as it is dull. Todd, the game’s hero, quickly brushes the idea aside, borrowing a play from the game’s irreverent humour and taking the narrative into his own hands. Todd is a but a tailor, as far as one can tell; unremarkable apart from his impressively sardonic expression. The pedestrian set-up wastes no time, however, launching into a distinctly satirical take on the classic hero’s journey as Todd finds a magical device that has him transforming properly spelled words into… magic. The specifics are unclear, but he manages to float trees, paint wool, decimate bricks and literally scare the scat out of unsuspecting monsters with a few well placed vowels. Its versatility is a lucky thing, as that’s just about all Todd has going for him.

He may not be the scariest monster, but give him time; he’s still green.

Every challenge your average adventure game would throw at you, be it the bashing of doors or doing of exceptionally menial chores, is handled through spelling. The game uses a traditional Boggle-esque grid, letting you swap tiles around at the cost of your limited meter, but looks to freshen things up by using your given activity to change the rules on you. Some of our favourite examples were having to find proper synonyms to “shear” Todd’s loyal sheep, or completing a bard’s pitiful attempt at music by filling in his blanks with some appropriately-rhymed words. The colourful world and adventures provide a clever context for the usually abstract toils of wordplay. while also managing to sidestep the usual fare of point-and-click head-scratchers that can leave many a player frustrated.

Not all of Todd’s quest is so linear, however. We found ourselves fighting monsters, collecting words, and trading our growing vocabulary for a variety of shiny objects. The blend of RPG and tile-swapping fun brought back memories of Infinite Interactive’s fantastic Puzzle Quest: Challenge of the Warlords; while Spellirium will be hard-pressed to match the hit’s polished ambitions, its influences are clear, and make a promising sign for Spellirium’s future. At the least, it’s looking to provide a more expansive quest than your average Monkey Island successor, which is some welcome experimentation for the genre.

Kill this monster and you might get a shiny a-word! That was a pun. Do I need to spell it out for you? I promise they’ll end sooner or letter.

Though the Alpha left us with promising concepts, it took some ample imagination to fill in the gaping blanks left by its still-unfinished state. Animations were choppy, bugs were frequent (the game froze hard on us several times), and sound was absent almost altogether. Some tweaks mechanically wouldn’t go amiss either, with an oddly forgiving loss system that allows limping through the challenges and side-content which serves more often as mandatory filler than rewarding exploration. What will go and stay in the coming months is up for money, time, and Untold Entertainment to decide; but they’ve got an exciting idea on their hands and the ambition to make it grand.

]]>

- Format: 3DS

- Unleashed: April 19, 2013 (EU), Out now (NA)

- Publisher: Nintendo

- Developer: Intelligent Systems

- Players: 1-2

- Site: http://fireemblem.nintendo.com/

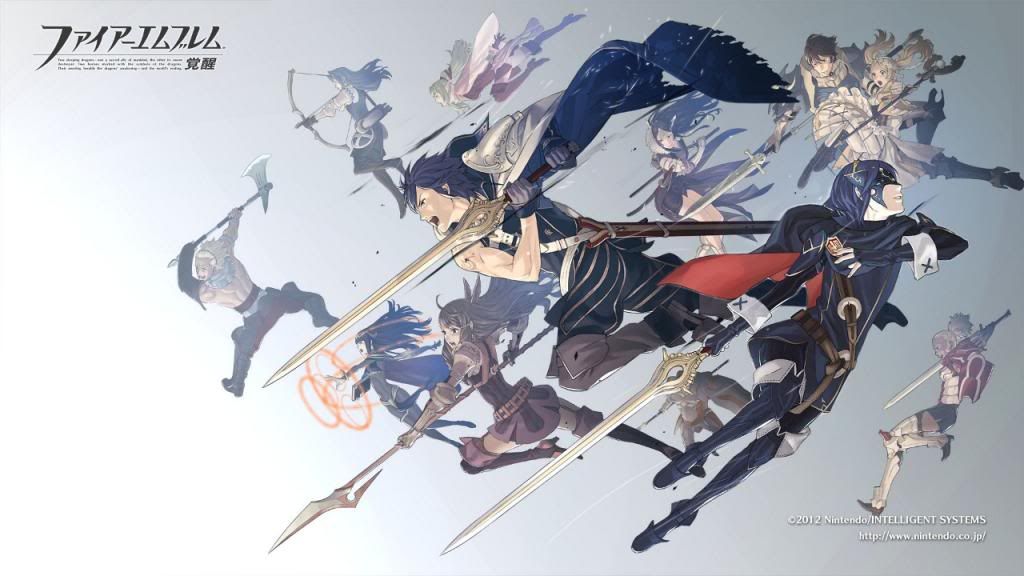

Dark prophecy looms over an already troubled kingdom, challenged only by a band of noble heroes dedicated to the ideal that destiny is not their inevitable master. This is an old tale, just like the legacy of turn-based tactics that guide its struggles forward, but Fire Emblem: Awakening strives to prove that a true legend is but a retelling; a fresh imagining of a more ancient time.

This was a time when sprites would dance about a grid, waging war with nothing more than the size of their Str stat and a few frames of animation. Awakening embraces this proud heritage of the strategy RPG with both an open heart and mind. At first glance, it seems to merely create accessibility, opening the daunting genre to a fresh audience with its lush presentation and introduction of the Newcomer Mode (a removal of the usual permanence of death for units). But those fearing an experience hamstrung by simplicity should soon realize their folly, because Awakening deftly manages to not only retain but enhance the gratifying complexity of the epics before it.

Awakening weaves quite the epic itself, telling the tale of Chrom, a blue-haired hero who exudes a depth and charm alongside his unwavering goodness and chivalry. As prince of Ylisse (no, it doesn’t get easier to remember), Chrom faces not only the threat of neighbouring warmongers, but an undead plague of mysterious origins. Where the formula departs from franchise norms, however, is in letting you create your own hero: a tactician to fight and plan alongside the more brash Chrom. He or she can be customized with a limited number of options but has set plot arc that’s surprisingly fulfilling, given the potential for generic filler here. It feels like a natural addition, aided by the game’s fantastic dialogue. The writing and translation do wonders for the game’s massive cast of colourful adventurers, managing melodrama and comedy with equal vigour in a plot spanning the largest of wars and most trivial of conversations, all of which which make fantastic bookends for the even more fantastic battles within.

That mage is soon to be as dead as whatever that hat he’s wearing is.

These wars are waged as they’ve always been, with your small band of growing heroes pitted against overwhelming (or, on the right difficulty level, whelming enough) odds, forced to rely on one another to survive the turns ahead. Play is managed with a traditional grid and bird’s-eye view of the lightly-detailed battlefield. Stats, weapons, items, and careful positioning all play crucial roles, but the meat of the strategy relies on the impressive array of classes and how well you’re able to leverage their varying abilities with one another to both stay alive and level further ahead. This lends an exciting vibrancy to the warfare as you watch your pegasus knight swoop down on an unsuspecting sorcerer, the precious XP getting your bar that little bit higher. However, the real connection with your troops comes not from their individuality as soldiers, but as people. Every unit you gain is a distinct character, with their own history, artwork, and, most importantly, support conversations.

Each character has a number of possible pairings that, when grouped together, will allow for a series of conversations that can lead either to a greater friendship, or in the case of opposite genders, eventual marriage. These serve a dual purpose, the first being the conversations themselves. The highlight of the game’s writing, these delightful skits serve as touching, personal, and often humorous insights into the cast and their varied relationships. They’d be an appreciable enough addition with just a handful, but the sheer volume of possible combinations is staggering, making it a truly admirable exercise in character development that few games even strive for. The second purpose is of a more practical nature: the greater a pair’s relationship, the larger their stat bonus will be when fighting together, which plays into Awakening’s greatest mechanical innovation.

Pairing up isn’t a complicated idea: it allows you to attach one unit to another. While you temporarily lose the benefit of two separate units, stat benefits are now allocated, and the attached character has a chance to get in their own attacks when combat arises. It isn’t a complicated idea, but the extent to which it utterly shapes the battlefield and your ability to survive it can only be experienced by having your favourite allies saved and fiercest foes slain by its graces time and time again. Instead of serving as mere bait for advancing enemies, weaker units can hide behind the strength of their superiors, allowing for a much easier use of a varied army. The simple system is a beautiful weaving of narrative and gameplay, elegance and depth, that leaves you stupefied that it could’ve ever been absent from entries past.

Friendship vanquishes all! An important life lesson in Awakening.

Awakening also attempts a foray into multiplayer and DLC, but these lacking inclusions do more to confuse than contribute. Quite an opposite effect is found in the game’s slick, near-flawless presentation. Apart from the curiously olden sprites splayed across the grid, every last detail feels finely honed with an expert eye for style and efficiency. Information is displayed intelligently across the bottom screen, relegating actual control exclusively to the buttons. Combat is effortlessly slid both in and out of with thrilling (and skippable) depictions of swinging swords and sparking spells, all with lovingly-animated polygonal models and screen-popping 3D put to excellent use. The symphonic melodies, laudable on their own, adapt seamlessly from combat to quiet, creating a cohesive flow to the action that Fire Emblem has been sorely lacking since the beginning.

Fire Emblem: Awakening proves well its compelling case that the past can be the future’s greatest ally, and vice versa. A few well-considered additions and a badly needed re-imagining of the presentation is more than enough to rekindle Fire Emblem’s well-deserved status as a gaming legend, and create a truly inspiring modern classic.

]]>

- Format: 3DS

- Unleashed: Out Now

- Publisher: Nintendo

- Developer: Intelligent Systems

- Players: 1

- Site: http://papermario.nintendo.com/

Those bored with pop-up books of the paper variety will be delighted at first to flip open their 3DS and be greeted by the stylish cheer of Paper Mario: Sticker Star’s wafer-thin world. Leafing through its digital pages is a delight rife with the series’ trademark enthusiastic charm, but smiles fade as the game’s flimsy mechanics unfold. Baffling design decisions that crumple every good idea prompt a question all developers should fear: what were they thinking?

Sticker Star raises this question at the most fundamental level: the basic systems of play underlying its clever jokes and snazzy scenery. Much is borrowed from its predecessors, throwing Japenese-style role-playing and Mario’s penchant for explorative jumping together to make what should be delicious results; the oddball recipe has worked remarkably well so far. However, Sticker Star does away with much of the former, streamlining itself into a patchwork puzzle-platformer that forsakes stats for stickers. Branching hubs and overworlds have given way to a world map dotted with linear levels, and while the series’ semi-active turn-based combat of timed button presses remains, it peels away layers of complexity until only the most basic remain. This shift would’ve been more reasonable if the new sticker system had more fun than frustration, but bogglingly broken combat and bogglingly boggling puzzles dash this wistful hope.

The stickers themselves descend upon the Mushroom Kingdom through the mystical Sticker Comet, a celestial rock that’s rumoured to make wishes come true. But Bowser will have none of it. Or, rather, all of it, as he makes a dash for the comet, splintering it into seven Royal Stickers that scatter across the kingdom’s seven world, giving him and his minions devious amounts of sparkle-speckled power. This spells trouble, and the ladylike sticker Kersti enlists Mario’s help to combat Bowser’s devious minions and regather the Royal Stickers. Unfortunately, Kersti serves as little more than an empty cipher for words the mute Mario can’t say; a tool that provides only the most basic means of story progression. Much like the game’s plot itself, in fact. Sticker Star’s story is not only utterly rote, but almost entirely absent. Actual storytelling is bookended at beginning and end, with nothing but blank pages between. For a series prized for its narrative romps, it’s a disappointing, even perplexing, oversight.

When he’s one of the main villains, you know story trouble is ahead.

The stickers do more than create a rote basis for story, however; they create a rote basis for combat. Paper Mario’s traditional trifecta of attacks, special attacks and items has been swapped out for the sole mechanic of stickers themselves, which basically operates by reducing everything to a single inventory. The touch screen becomes your album, displaying the variety of jumps, hammers, and mushrooms that make up the meat of your inventory. Though each can only be used once, there are enough pasted across the levels that the problem quickly shifts from filling your album to managing its limited space. Tapping out attacks is amusing enough, but absent complexity and effortless button prompts keep it from rising above novelty. Some variety comes in the form of oft-oversized stickers created from random things (called, appropriately, Things) found strewn throughout the kingdom of mushrooms, be it a pair of scissors, a refrigerator, or the odd giant goat. (And really, it’s odd.) But while their animations are endearing and lovingly crafted, like much of the game, their similar effects add little to what’s, ultimately, a dreadfully dull way to do battle.

This could’ve been a forgivable offence; plenty of RPGs are choosing to streamline, and one as kid-friendly as Paper Mario is especially entitled to such a shift. However, the combat’s not only shallow; there’s no actual reason to do it at all. Apart from the few mandatory bosses, every fight in Paper Mario can be avoided, or at worst, fled from. Previous games have handled this by incentivising you to fight, be it through character progression, greater convenience, or barriers to retreat. Sticker Star uses none of these. Instead, with leveling and experience points taken entirely out of the equation, battles reward you solely with stickers and a few coins (with which to buy more stickers; a deviously one-sided economy). These make somewhat useless rewards, since you’ll have plenty of each either way. Simply tapping the always-available ‘run’ button is the far more inviting option, which is consistently successful the first or second try. Add on top of this that it carries no penalty beyond wasting a turn and it effectively removes combat itself as anything more than an entirely optional, and unfortunately dull, distraction.

With goomba-stomping out of the picturebook, Sticker Star leaves you with its unorthodox combination of fixed-perspective jumping and item-based puzzling. The game’s platforming doesn’t stray far, or even at all, from its roots, which means it’s… fine. Not interesting, or even very enjoyable on its own, but fine. Merely a simple way to jaunt from point to point, weaving between two-dimensional vagabonds until progress is blocked by another of the game’s sticker-centric innovations: the puzzles. Kersti grants Mario her unique ability to Paperize, allowing him to step outside the world to peel and plant stickers at particular spots. This mechanic is the basis for most of the game’s environmental head-scratchers, and also for its most maddening frustrations.

The most aggravating of these is the game’s use of Things as their solutions. A given quandary will often require a specific Thing, which could be just a screen or two away, or in another World entirely. While we admire the game’s unconventional thinking when it comes to solution and direction, rather than just guiding the player with a patronizing, yet charmingly cute hand, clues tend to range from nonsensical to non-existent. The answer could hide among any of the dozens of side-paths and secrets littering Sticker Star’s abundant levels; worse, even testing a sticker will use it up, discouraging any experimentation, as you’ll need to trek all the way back to find it yet again should you need it later. Minutes can stretch into hours as a given string of searches drags on until the game feels more padded than the cell you’ll inevitably find yourself within by the end. It makes the reasonable length (upwards of twenty hours) something of a farce. It’s truly a shame to see an attempt at defying linearity and the “plays itself” mentality muddle itself so thoroughly; a shame heightened by just how lovable Paper Mario: Sticker Star is.

Kamek has a great theme song. That alone is an incredible feat.

Even when hating it you can’t help but to love it. While not so ridiculously creative as instant classics like 2004′s Paper Mario: The Thousand Year Door, Sticker Star doesn’t skimp on its clever wordage and vibrant personality. Its cast of near-identical toads surprise and delight with their vast vocabularies and distinct outlooks, spouting a good share of laugh-worthy lines incidental to the disappointing plot. Though usually focused in the game’s capital of Decalburg and a few outlying towns, welcome character occasionally spruces up the all-too-generic levels themselves. The world’s blandness is further lessened by the series’ trademark art, bursting with colorful cut-outs. Though showing a choppier frame rate than its predecessors, 3D is handled with the perfection one would expect from such a suitable showcase for its eye-popping tricks. However, what’s most noticeable, and laudable, is Sticker Star’s energized and exceptionally-produced soundtrack.

Those despairing of Mario’s slide into musical mediocrity should be as delighted as we were to hear the jazz-infused genius of Sticker Star’s abundant melodies. Each echoing snare and slap of bass rings with heart and style, bringing even the drabbest desert or jungle gleefully to life. Even long-overplayed remixes are revived with a meticulous balance of new and old. The game isn’t shy about embracing its stellar backing, either. Bosses clap along, mariachi guys (of the shy guy variety) add their strummings, and certain songs blend and form to match your surroundings, carrying the proud tradition of such musical wonders as Banjo Kazooie years before. While no soundtrack is perfect, Sticker Star’s comes dangerously close, simultaneously innovating and superbly capturing an already well-established series.

Paper Mario: Sticker Star does so much right, but gets too much wrong. A sound premise and lively presentation are ultimately unsupported by their paper thin foundations. What few pages of depth exist are revealed to just be stuck together, and by the time the painful process of peeling them apart is over, you’ll wish they’d just been ripped out to begin with.

Those in London hunting for a Wii U and an appropriately crowded venue to nab one may be happy to hear that retailer HMV is hosting an Official Wii U Midnight Launch. They’ve partnered with Nintendo to offer a chance to grab consoles free of pre-orders, so it sounds like a first-come-first-serve basis will be the rule instead. A variety of rewards and game demos from Ubisoft and Nintendo will also be available, to make more palatable the idea of waiting around outside in the middle of London on a late-November night, we suppose.

The doors will open on Thursday, November 29th at 11:00 PM and shall take place at 150 Oxford Street’s HMV.

]]>

In an age where patches can make news, Ubisoft’s latest patch has made news. Yesterday on their forums, Ubisoft released an exhaustive list of changes next week’s patch will bring to Assassin’s Creed III. The tweaks cover the spectrum, ranging from fiddling with multiplayer modes to removing Benedict Arnold’s icon from the map legend, and will hopefully provide some relief to players frustrated by the technical issues so far.

The full patch notes can be read here and the patch’s release is slated for the end of next week. For a critical analysis of the game itself, click your way over to our Assassin’s Creed III review.

]]>

- Format: PC

- Unleashed: Out Now

- Publisher: Daedalic Entertainment

- Developer: Daedalic Entertainment

- Players: 1

- Site: www.daedalic.de

“It’s about Lily, the most virtuous child in the entire world.”

It’s with these ambiguously sarcastic words that the narrator ducks convention and Harvey’s New Eyes begins to unveil the unsettling tale that is to come. An unassuming (and certainly unexpected) protagonist, Lily begins as the perfectly behaved schoolgirl that waddles her way through a point-and-click adventure, chatting up the local loonies, using and combining a baffling bevy of items, and performing the other expected duties of such a hero. What’s unexpected is the trail of morbid destruction left in her wake.

This dark fate is unimaginable when you first see the delicate and lovable little girl Lily dutifully raking leaves at her convent home. Something we can all relate with… or those of us raised in German religious institutions at, least. But this is but a ruse. Every puzzle solved and glimpse into Lily’s sweet yet shadowed mind rips back the shreds of cheer like an especially rotted onion. Her twisted naivete shrouds startlingly dark realities that are commented upon with the sickly sweet sarcasm of the narrator (who, though skirting irritation with his overacted cynicism, makes an effective and clever voice for the usually-mute Lily). This makes the quest that unfolds to save Edna, Lily’s only real friend, from a maniacal psychologist just a backdrop to the show’s real stars: A questioning of the constraints of conventional morality, and Lily’s own disturbing little mind.

Lily uses her mind for more than to backhandedly wish doom upon the world, however. Mechanically quite ordinary, there are puzzles to solve that deliver just what’s appropriate for the genre. While rarely treading the path of genius, they offer a satisfying balance of complexity and intuition, with a definite knack for weaving clues into the abundance of well-voiced dialogue. Careful listening and observation yields success far quicker than a mad click-fest of trial and error, inviting the player to examine everything and hear the many humorous, self-aware quips that have become a delightful hallmark of the genre.

The game even branches out with its own original mechanic: a variety of moral restrictions invoking everyone’s stereotypical childhood taboos. Playing with fire, contradicting adults, and six others comprise the list, though only one barrier can be lifted at once. This shows promise; but while unlocking each restriction serves as its own self-contained puzzler, they’re rarely referenced again, and having to swap them out is more useless than anything. The game instead sticks to what it does best: the tried and true method of picking everything up and madly hoping you’ll know what to do with it. Unfortunately, it’s not a complete stranger to inconsistent logic (something it rather brilliantly points out itself), with the potential to easily frustrate. What the puzzles result in is where our eyebrows began to loft once again. A nabbed key or unlocked door will often carry with it an unsettling and grisly death; one you clearly caused, despite the game’s winking naivete.

It’s this surprisingly blatant sense of the macabre that oozes from the game’s every line and action. It makes a black contrast to the surreal silliness instilled in this troubled world. Characters have the absurdities expected from a Monkey Island, but with a dash of the unpleasant or insane that makes one question them each in turn; the art is a jumble of piecemeal proportions and perspectives, which could be charming if not for the subdued colour palette; and the music has a jaunty jazz beat that’s kept to the melancholy or downright creepy.

Though the striking contrast certainly makes the world stand out among its more merry peers, for good or ill, such liberal use of darkness doesn’t come without a price. The troubling psychosis of the demure Lily, which is hinted at but never defined in the first chapter, is rushed by in the next two, concluding in an unrewarding and over-explained trio of possible endings. Both premise and tone set up intriguing expectations, but failing to deliver leaves them merely haphazard and overwrought for such an otherwise conventionally carefree game. Why did Lily perform these horrors? What were all those deaths even for? Is that lunch lady verifiably insane or just a jerk? Half-answered questions trail listlessly into a conclusion that makes you wonder if Daedalic ever even cared about the answers.

While Harvey’s New Eyes may fail in its loftier ambitions (assuming they were even there; perhaps being twisted is its own reward), it’s in tinkering with tradition that it makes a game well worth playing. Tackling substantial puzzles and oddball humour with a practised air of know-how, Daedalic created a memorable show of point-and-clicky goodness; just one that may leave you staring in uncomfortable silence.